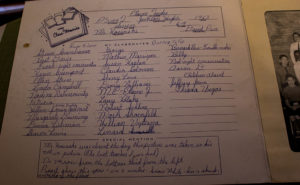

1964 Public School 149

1964 Public School 149

Elaine inched her hand up to get Mr. Kozinski’s attention at the blackboard.

“Yes?”

“I forgot my glasses. Can I move up closer?”

With a nod from the teacher, Elaine grabbed her book bag and bee-lined to an empty desk next to Bernard. As school busing loomed over the Jackson Heights and Corona school districts, there were five black kids in the predominantly Jewish sixth-grade classroom. Elaine, one of the few Catholic students, had a crush on Bernard—tall, slim, dark brown skin— a troublemaker, which made him all that more interesting. Too young for any serious romance, they teased and cajoled each other whenever the opportunity arose.

“You gonna sit there?” Bernard whispered.

Elaine smiled, shrugged, and purposely brushed her friend’s shoulder as she maneuvered in place. Bernard crumpled a piece of loose-leaf paper into a ball and tossed it at Elaine’s head. She ducked it before Mr. Kozinski turned from the blackboard where several math problems now presented themselves.

“Okay, you two, settle down,” he said with a slight grin. He kept a vigilant eye on the two students, not out of disfavor, but concern for their welfare—worried that their innocence may get them in trouble as the civil rights movement escalated. If only they were the same color, they may stand a chance.

* * *

As the school year ended, the hotter weather called out for ice cream. The local soda fountain had the best chocolate chip, scooped into sweet, waffled sugar cones. Elaine and Bernard joked about the chocolate blended into the vanilla flavor as if at some point they might melt into one shade. With cones in hand, the two youngsters perched themselves on the two horses of a coin operated merry-go-round outside the store. Neither had ever seen anyone put money into the thing, but it had an umbrella and the shade felt good.

“So, what are you doing this summer?” Bernard asked between licks.

“Not much. Probably knock around the schoolyard. I’m getting pretty good at handball, although my mother says that it will give me arthritis in my old age,” Elaine replied.

“What a weird thing to say. How does she know? Is she a doctor?”

Elaine shrugged, “No matter what I do or say, it’s wrong and there’s some reason that I shouldn’t do it. Anyway, she doesn’t know what I do all day while she’s at work. Last week I took the train out to Coney Island and got back in time for dinner. They never knew that I wasn’t around the neighborhood.”

“Well, maybe we could meet up and go to the World’s Fair. I know how to sneak in by climbing over the back fence”

“Hmmm, maybe. Been there so much already, it’s getting kinda boring.”

Out of the corner of her eye, Elaine thought she saw a black Ford Impala sedan cruise slowly by; the same model her dad, Teddy, drove. “I better get home. I think that was my dad’s car. Usually he’s home from work earlier than this.”

“Okay, well, I’ll see you around,” Bernard said as he tossed his napkin in the nearby trash can.

Despite the heat, a shiver ran up and down Elaine’s spine as she watched Bernard saunter away. It probably wasn’t her father in the car.

* * *

Elaine fumbled for her house-key and was surprised to find the door to her family’s second story apartment unlocked. She hoped that her sister might be home, but as she climbed the long staircase and walked by the living room into the dining room, she was confronted by Teddy.

“I saw you with that nigger,” he started. “I told you, to stay away from those people, they’re not like us and if I see you with him again, you’ll be sorry.”

Elaine knew she should keep quiet but decided to try and reason with him. “He’s just a friend. We hang out sometimes. Today we stopped for ice cream. There’s nothing going on.”

“I don’t care, he’s a black and you’re white, so stay away from him. I had Mike in the car with me and he couldn’t believe that I let you hang out with niggers. I’ll never hear the end of it if he tells the other guys at work.”

“But, you work with black men. Why would anyone care?”

With Elaine’s last statement, Teddy’s face turned red and she knew she went too far. She needed to learn to keep her mouth shut. Then she smelled the alcohol on her father’s breath and looked around for an escape route. Teddy blocked her path as she tried to slip past him. If she could get to her bedroom, he might leave her alone.

“Smack!” Elaine caught the open-handed slap towards the back of her head. There would be more—she had to think fast. Her bedroom door didn’t lock, so she made a run to the bathroom, pushed the door shut and turned the bolt.

“Come outta there, now!”

“No,” was all she could get out between shivers. She prayed that the door would hold up to the banging. She glanced at her watch—5:30, her mom should be home from work soon.

“Teddy!” she heard her mother, Alice’s voice—thank God. “What’s going on in here?”

“She won’t come out of the bathroom.”

“What? What’s she doing in there?”

“Me and Mike saw her with that black boy again and I’ve told her before to stay away from him.”

Alice, set her purse on the dining room table. “Have you been drinking with your buddies again after work? You’re supposed to be making dinner, not fighting with Elaine.”

Teddy cowered and plopped down in one of the chairs near the table. He had promised to give up the weekday drinking—always got him in trouble with the wife. Alice jiggled the handle on the bathroom door. “Elaine? Come out of there, now.”

Elaine cautiously opened the door. Her mother’s frown said it all. She imagined the conversation they would have later. She’d be pissed, he would grumble—in the end they’d agree that the black boy was bad news, but that he shouldn’t hit the kids. Elaine slipped by and collapsed on her bed. Dinner would be late and with any luck Teddy would skip it and sleep off the booze.

* * *

Elaine jumped when Bernard’s voice came from behind. “So, why haven’t I seen you lately?” he asked. It was halfway through the summer and Elaine had been avoiding her friend. She had no idea what to do about anything.

“Oh. Dunno. Been busy.”

“Doing what? I’ve been checking the handball courts. You haven’t been anywhere I’ve looked.”

“My parents won’t let me see you.”

“Why?”

“You’re black.”

“You’re kidding, right?”

“No. I’ll get in trouble.”

“So, what. We’ll meet up someplace else. Maybe Astoria pool?”

“I can’t. I’m afraid.”

“What can they do to you?”

“Hit me.”

“Your father hits you?”

“Only when he’s drunk—which is more now. And my mother backs him up on the black thing and she’s not always around when he’s mean.”

“So that’s it? We can’t hang out anymore?’

“I’m sorry, maybe someday.”

* * *

That someday never came. Elaine became braver and argued with her parents. She became expert in doing what she wanted and lying. Verbal abuse escalated and her mother, to regain control, manipulated her husband into more violence. Nothing made sense. One month after Elaine’s eighteenth birthday, she left home and moved 3000 miles away—the family never recovered.

ShareAUG

2021

About the Author:

Elaine Webster writes fiction, creative non-fiction, essays and poetry from her studio in Las Cruces, New Mexico—in the heart of the Land of Enchantment. “It’s easy to be creative surrounded by the beauty of Southern New Mexico. We have the best of everything—food, art, culture, music and sense of community.”